Image Credit: Stephane Cardinale - Corbis / Contributor / Getty Images

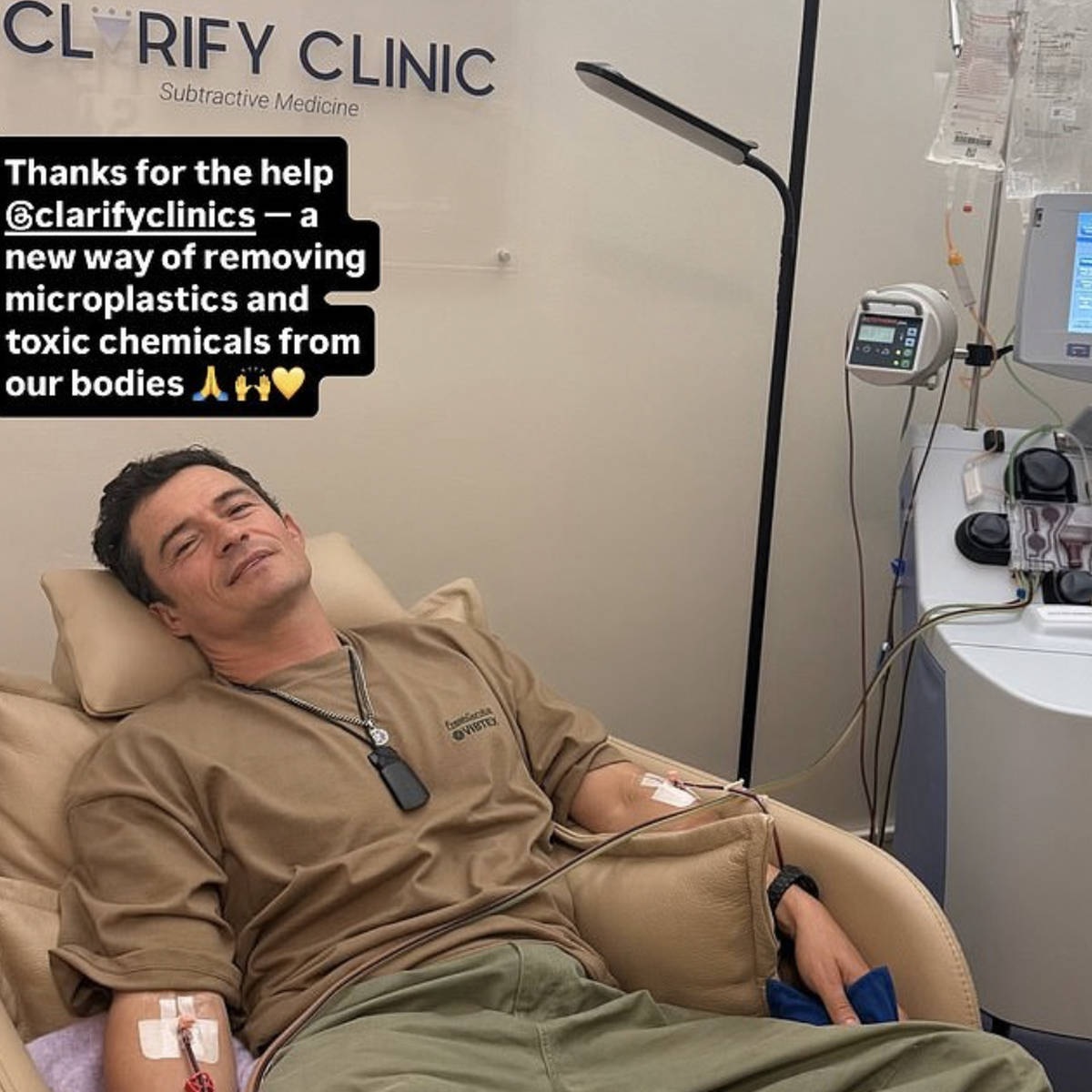

Image Credit: Stephane Cardinale - Corbis / Contributor / Getty Images At the beginning of last month, it was widely reported that the Hollywood actor Orlando Bloom underwent a £10,000 treatment to remove microplastics from his blood.

Bloom posted a picture of himself at the Clarify Clinic off London’s Harley Street, hooked up intravenously to a filtration machine of some kind—perhaps a hemodialysis machine, which would typically be used by sufferers of kidney failure.

Here’s some of what The Daily Mail had to say about Bloom’s treatment.

He helped defeat Sauron in Lord of the Rings and has sailed the seven seas in Pirates of the Caribbean.

And Orlando Bloom’s latest adventure may sound like the plot of an equally fantastical film – except it’s real.

The star looked very relaxed as he was hooked up to a machine that is claimed to remove microplastics from the blood.

The London clinic offering the £10,000, two-hour treatment was praised by the actor, 48, for ridding his body of ‘toxic chemicals’.

The Mail goes on to explain, in general terms, how the treatment is supposed to work.

During the treatment, blood is extracted from the arm and split into red blood cells and plasma. This plasma, according to David Cohen, the inventor of the procedure, is then cleansed of its ‘forever chemicals, the microplastics, the inflammation and the poisons and toxins’ with a machine before being mixed with the red blood cells again and put back into the body.

Clarify Clinics is said to be the first in the world to offer the service, called Clari. It is claimed to remove between 90 and 99 per cent of microplastics from the blood.

Clinic bosses say the procedure—which is not covered by the NHS—reduces inflammation in the body, which has been linked to cancer and neurological disorders.

The claims made by Bloom and the Clarify Clinic have been greeted with a significant amount of scepticism, but there’s absolutely no reason to believe blood filtration wouldn’t work to remove microplastics from the blood. If you remove blood from the body, put it through a filter that’s finely graded enough to catch microplastics, then return it to the body, the blood would contain fewer microplastics.

The main issue really, from a technical perspective, would be the filter itself. Microplastics come in a wide variety of sizes, from particles that are visible to the eye (5mm), to particles that need powerful imaging technologies to be seen. We’re just starting to learn about a new, even trickier, class of microplastics called nanoplastics, which are even smaller (smaller than one micrometre, or one thousandth of a millimetre) and potentially cause much more damage within the body because they can get into even tighter spaces than microplastics. Nanoplastics would require tremendously fine filters to catch.

There are some other practical problems that deserve consideration too.

Clarify Clinics haven’t provided any details about the machines used, but as I mentioned at the beginning, it’s likely to be something like a hemodialysis unit used by sufferers of kidney failure. This class of machine is called an apheresis machine. They’re also used in a number of other treatments as well, such as removing cholesterol, toxins or antibodies that trigger autoimmune diseases. They can also be used to collect cells from the blood, such as stem cells or platelets, for transplants.

One problem with these machines is that they actually introduce microplastics directly into the bloodstream of users, because they contain plastic parts and use plastic tubing to circulate the blood. In the picture posted by Orlando Bloom, you can clearly see plastic tubing leading from the actor’s arm to the machine and back, and you can also see that the machine itself is made of plastic.

Just how big a problem is this? A study this year in the journal BMC Nephrology looked at 30 samples of dialysis solution—a solution designed to mimic the composition of blood plasma—using advanced imaging techniques. Microplastics were discovered in every single sample. Polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride and ethylene vinyl acetate were the main types. These are all types of plastic used in dialysis machines.

The researchers write: “These findings suggest that packaging-related polymer degradation and leaching may be one of several contributing sources of microplastic contamination in dialysis solutions necessitating further investigation into mitigation strategies and alternative material development. This aligns with existing literature demonstrating that polymer degradation, occurring through environmental stressors and mechanical handling, can introduce MP contaminants into pharmaceutical and medical solutions. Given the extensive handling, transportation, and storage conditions to which dialysis solutions are subjected, the potential for MP contamination is considerable. These findings underscore the necessity of stringent regulatory oversight and the development of alternative, biocompatible materials to minimize polymer migration and enhance dialysis fluid purity.”

There’s an unpleasant irony to these findings, because sufferers of kidney failure are likely to be even more vulnerable to the effects of microplastics in the blood than normal people.

Other studies are showing that medical equipment in general is an underappreciated source of exposure to microplastics. A recent study of intravenous medical bags has shown that a single bag of infusion could release 7,500 microplastic particles into the bloodstream. During procedures that require multiple infusions, the number of microplastics transferred could be significantly higher. The researchers calculated that a typical abdominal surgery might introduce over 50,000 microplastic particles directly into the blood of the patient.

It’s not just microplastics either. Medical equipment also transfers harmful chemicals to patients, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals like phthalates, often at alarmingly high levels, and directly into the bloodstream, without the protections afforded by the digestive system.

One study in the journal Pediatrics noted a spate of five cases of deep-vein thrombosis—blood clots—among children in a single ICU unit after they had catheters inserted. Deep-vein thrombosis can easily be fatal if it isn’t caught and treated quickly, and there’s basically no reason why a child should suffer this condition, except in the most unusual circumstances.

The researchers discovered that the cather tubing itself was releasing large particles containing a chemical called di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate or DEHP, and they suspected that this was responsible for the clotting. Transfer of DEHP from medical equipment to patients, by means of everything from surgical gloves to medical tubing, has been identified as a potential aggravating cause in a wide range of conditions, from contact urticaria (localised swelling and redness) to adverse heart effects.

A study from 2023 took samples of 72 single-use medical products used in an intensive-care unit and showed that every single one leached DEHP, including products that were labelled “DEHP-free.” Worryingly, the highest levels were found in products used on premature babies. These levels exceeded maximum tolerance levels.

The researchers note: “Exposure doses of newborns to DEHP from medical devices exceeded the tolerance levels set by the FDA, under the maximum exposure scenarios. It should be noted that our exposure calculations from the devices assumed incidental and single-use scenarios, but frequent and long-term exposures can occur among patients.”

So, far from cleaning Orlando Bloom’s blood of microplastics and toxic chemicals, the “Clari” treatment he paid £10,000 for may actually have introduced microplastics and toxic chemicals into his body. I’d ask for a refund.

What would be needed to perform this procedure effectively—and like I say, there’s no reason to believe it couldn’t work—is an entire apparatus that contains no plastic or harmful chemicals like DEHP. That would be the only way, as far as I can see, to avoid contamination during the filtration process itself. Whether such a machine could be built, I don’t know.

Then again, it might be the case that, even if these treatments with these imperfect machines return microplastics and toxic chemicals to the blood, the overall toxic burden is reduced. But we simply don’t know at this stage.

That’s why I believe it’s imperative for there to be new research into treatments for microplastic exposure, as well as research that establishes, definitively, basic thresholds for exposure, the most common sources of exposure, and the most effective ways to minimise it. Even now, after years of growing worry about microplastics, we still don’t know answers to basic questions like how many microplastics is too many? Or what proportion of microplastics I ingest end up in my blood—and what proportion of those end up in my organs?

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has spoken at length about the threat to health from microplastics, and now that he’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, he has the perfect opportunity to do something about it. He’d have no end of willing participants, not least of all in the online health sphere, to take part in his research.

This essay was taken from Raw Egg Nationalist’s Substack page, In the Raw. Subscribe now for full access to essays, podcast interviews, detailed analysis of new scientific studies and much, much more.