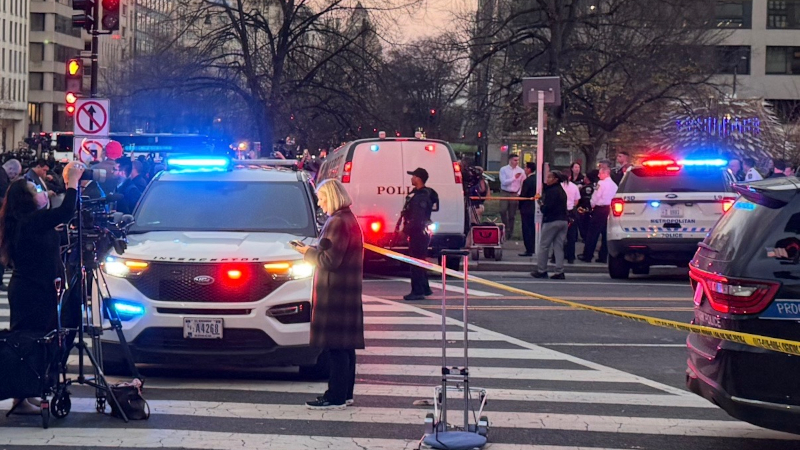

Image Credit: Wid Lyman | Border Hawk

Image Credit: Wid Lyman | Border Hawk Officer R greets me at the entrance to the First District Station of the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia (MPD).

“I love this job,” he states as we shake hands.

The lobby is barren like most stations but there is a remembrance wall for the 31 officers who have lost their lives while in service to the First District (1D). A message reading, “It is not how these officers died that made them heroes, it is how they lived,” is inscribed on the wall along with a police badge and a red flower emblem. Most recently, 25-year-old James McBride died during a training incident in 2005.

Officer R escorts me toward a waiting cruiser, slides into the driver’s seat, and revs the engine. The SUV starts right away, but the check engine indicator lights up immediately.

“I need to take it in for service at some point,” R says.

The 1D headquarters sits smashed between a park and subsidized housing in the southern part of the city. 1D is unique in D.C. as it encompasses Nationals Park, Capital One Arena, and Audi Field. Just to the north is the National Mall, U.S. Capitol, rows of museums, Supreme Court, and Congressional office buildings. Heading east one will find the now-infamous Navy Yard and to the west is the waterfront region known as the Wharf.

“You get everything here in 1D,” R explains as we roll along back streets. “Tourists, events, government agency calls, car accidents, transit issues, you name it. You have to be ready for anything.”

16:03 — Traffic is picking up as folks commute home in the frigid afternoon air. We pass a group of National Guardsmen patrolling along the Mall, and I ask R if anything has changed since the shooting that took the life of one Guard soldier and left another in critical condition.

“I believe some of our team will be patrolling with them. We always keep an eye on them and they on us. Really good people, and they are actually very helpful. Another set of eyes actually goes a long way in a town with lots of cameras,” R says.

We will soon find out just how helpful they really can be.

I’m amazed at the sheer volume of law enforcement we see during our drive. We encounter other MPD officers, Secret Service, Transit Police, Park Police, Capitol Police, Museum Police, FBI, and U.S. Border Patrol in just the first 30 minutes. They all have assigned areas and duties, but overlap does exist.

“We have great relationships with other agencies, and they often defer to us, especially in homicide cases,” Officer R says.

17:08 — The first call comes in: a domestic dispute where the caller reports being slammed into a bookshelf by a family member in a condo unit in the heart of Chinatown. R hits the lights and we zip over to the building a few blocks away. Another officer arrives and we head for the door.

We are greeted at the elevators by a barefoot young man with a black eye in obvious distress. He reports being assaulted by his family member and wants the police involved. R and his fellow officer ask to see the unit and we head up. The front door has been smashed and the condo is a wreck, with several cats roaming around. The bookshelf has seen better days, and there’s dried blood on the floor.

The details of the story are convoluted, and officers attempt in vain to get to the bottom of what happened. R tries gamely to get a description of the family member.

“Well, how tall is he?” R asks.

“How tall are you?” the young man retorts.

“Six feet,” R says.

“Are you really?” the guy responds.

“Yes,” R confirms with an eye roll.

Additional baffling details are relayed and I am more confused about what happened than before we arrived. R and the other officer take copious notes and we head out. I am shocked that people can live in such squalor and neglect, under the oppressing smell of cat waste that lingers in my nose for hours.

“I am ready for a coffee. You?” R asks as we load back up. I’m always ready for coffee.

R places his red Starbucks cup in between two stacked rolls of caution tape.

“I am working on getting cup holders one day,” he says.

We head to the courthouse to check on reports of a protest outside the building. Upon arrival, we learn it’s a citizen group that assists detainees leaving the court. They are harmless but we drive over to two unmarked vehicles to see if any assistance is needed.

“What are you waiting for?” R asks.

Another officer points at me and says, “Waiting for that guy next to you.”

I lean forward in surprise and ask, “Me?”

“The reporter?” R clarifies.

The other officer says, “Oh, I thought he was a Fed.”

This is not the first time I have been mistaken for a federal agent. I show him the “PRESS” placard on the front of my ballistic vest.

He asks what outlet I am with.

“Border Hawk,” I reply

He lights up and says, “I have heard of you guys. Big fan.”

I give him a Tom Hardy thumbs up and we roll out.

18:08 — Metro Transit Police is requesting assistance for a juvenile in distress at the L’Enfant Plaza metro station. We race over and park outside one of the three entrances. We hurry down the escalator and reach the turnstile. There’s no guard to open the gate for us and we pause. Hopping the gate is one option or R has to lift the emergency gate on the inside and wait for the alarm to turn off.

I take out my metro card and scan in, and then offer it to R. He laughs and says he’ll wait. We finally get through and I ask with consternation, “You guys don’t have a pass of some variety to get into the metro?”

“Nope. They do in Virginia but not here,” R says.

The Plaza is packed with hundreds of travelers. We approach the transit officer who will be assisting us and locate the juvenile. The young man is upset about something, but isn’t communicating clearly with officers. He tells a story about seeing “his girl” with other people and getting mad about it. It’s unclear how law enforcement was contacted, and after a few minutes, he hops on an outbound train. Another team of officers and EMS personnel arrive, and after a brief conversation everyone leaves.

I am once again shocked at how many different agencies respond to calls and wonder how any crime happens in the city at all.

We exit the area and are passed by more secret service vehicles and a convoy of federal agencies who make up the D.C. Task Force. Homicides in the district hit 124 this year, a 29% drop from last year. The decline has been attributed to extra law enforcement working in the district and the presence of the National Guard.

In early August, just before the deployment, D.C. had improved upon last year’s homicide numbers by only 13%. Uniformed officers on patrol and armored vehicles positioned at places like Union Station have become common sights since President Trump declared war on D.C.’s crime issue.

U.S. Marshals Service Director Gadyaces Serralta believes D.C. is now safer following the crackdown.

“I think this operation is a continued success,” Serralta told 7News reporter Nick Minock.

“6,127 arrests. 600 guns, illegal guns taken from folks who shouldn’t have guns. [President Trump] made the U.S. Marshals Service the lead agency in coordinating. However, the work is done by all 31 agencies, including the Metropolitan Police Department. So, the secret there is un-handcuffing the law enforcement officers and letting them do their work. Let them enforce the laws that are in the books.”

D.C. has a variety of rules and laws that govern what MPD can and cannot do, including when to chase suspects — particularly on scooters, of which there are many in the District. A police chase in 2020 resulted in the death of Karon Hylton-Brown. An MPD officer was subsequently convicted of second-degree murder, conspiracy to obstruct, and obstruction of justice. He is the only officer to ever be charged and convicted of murder while on duty in D.C.

MPD personnel feel the restrictions on policing are too extreme and a return to constitutional laws would be optimal.

“Everything changed after COVID,” an MPD source told Border Hawk.

19:03 — We receive a call for a possible overdose outside of a Safeway market and R takes it, blasting lights and sirens as we head across town. We arrive and there are already other units, EMS, and National Guard troops on scene. A distraught man is being loaded onto a gurney, and we learn one of the soldiers saw the man in distress and administered Narcan, which possibly saved his life. Naloxone, known more commonly by the brand name Narcan, is a medication used to reverse opioid overdoses and is delivered as nasal spray.

Four Guardsmen from a southern state are attentive as they help the man. They are sober and watchful as people hustle past. We offer thanks for their service and condolences for their fallen solider and head back to the patrol vehicle.

Meanwhile, a group of 15-20 people are gathering to protest the federal deployment in D.C. The troops head to their vehicle to wait for the protesters leave. The fact that these agitators had the gall to target American soldiers moments after they potentially saved a man’s life leaves a worse taste in my mouth than the cat waste.

The caution tape cup holder is holding up well as R sips his coffee with the windows cracked. He knows the streets and his district well. He knows the “bad” spots and areas that need extra attention. We pass possible drug dealing, suspicious vehicles, check on an elderly woman with balance issues, and back up other officers before the last call of the night.

19:37 — Transit police are requesting assistance for a possible missing juvenile who disappeared near a metro station. Upon arrival, we meet the parents who explain that the child jumped out of their car during a disagreement and ran off. Transit police report that a thorough search yielded nothing and R launches into investigation mode, calling other officers, getting statements from the parents, phoning children’s hospitals, and putting out notices with the juvenile’s description.

The juvenile is labeled as “critical missing,” and the gears of the city begin cranking as the search heats up. We gather intel and learn the juvenile may have fled to the Wharf area, so we light up the cruiser and head down to search.

There were 1,341 total cases of missing people in D.C. as of July 2025 – 958 being kids. That’s more than four per day.

We arrive at the Wharf and several other officers are there doing high-visibility work with lights flashing. The parents arrive, and after a very confusing 15 minutes, it is determined that the child has been located. We get back in the cruiser, and after R spends time on the phone with high-level MPD officials, the case is quickly closed.

We roll back to the station and R drops me off at my vehicle. I thank him for the opportunity as I get out.

“Best job I ever had,” he reminds me.