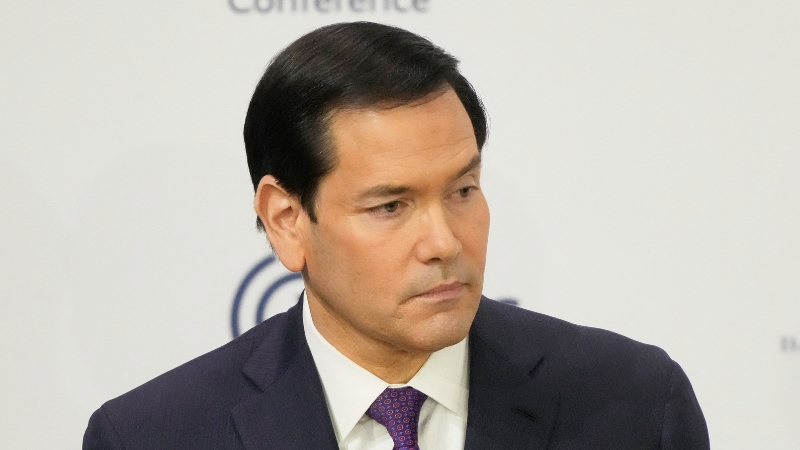

Image Credit: OLIVER CONTRERAS / Contributor / Getty Images

Image Credit: OLIVER CONTRERAS / Contributor / Getty Images “Seventy percent of Americans are either obese or overweight, and it’s not because they got indolent or because we became lazy or because we suddenly developed giant appetites. It’s because we’re being given food that is low in nutrition and high in calories and it’s destroying our health.”

Those were the words of Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who was interviewed for a 60 Minutes special on ultraprocessed food that aired on Sunday.

Kennedy has made ultraprocessed food one of the main targets of his holy crusade to “Make America Healthy Again.” The average American now derives more than half of their daily calories from a type of food that didn’t even exist a hundred years ago; reams of scientific research have linked it to every chronic disease you can name, from autism and Alzheimer’s to cancer, diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome.

As I try to drive home in my work, again and again, the twentieth century witnessed a change to diets that was as dramatic as any in human history, including the Agricultural Revolution in the Near East, ten thousand years ago. The profound sickness we see all around us today is a direct result of that change.

The 60 Minutes special is well worth your time if you want to know more about ultraprocessed food (alternatively, read my detailed primer here). Kennedy was joined by former FDA head Dr David Kessler—who said human biology has no effective defenses against energy-dense, “hyper-palatable,” addictive processed foods—and by Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, a book I consider to be one of the most quietly radical books about food ever written. Pollan had some very interesting things to say about the incentives that drive the production and consumption of cheap ultraprocessed food, especially the subsidies that support massive overproduction of corn and soy in the Midwest. Corn and soy are the two most important inputs for ultraprocessed foods in the US today.

One of the main targets for Kennedy during the show was a system known as GRAS, an abbreviation for “Generally Recognized as Safe.” You’ve probably never heard of it. Kennedy said GRAS is one of the main reasons why ultraprocessed food in America may be the worst in the world.

He’s right.

GRAS makes it impossible to know which food additives are safe and which aren’t, because barely any have been given thorough independent safety-testing.

Worse than that, the system makes it impossible to know how many food additives there are in the first place. We simply have to guess, because producers aren’t obliged to tell the FDA, so long as they—the producers—decide their new creations are safe.

Fox, henhouse—I think there’s a saying…

Here’s a little more about what GRAS is and where it came from.

GRAS was first introduced by the FDA in 1958 after the passage of the Food Additive Amendments. The aim was to “grandfather” through additives that were already in use, without further safety testing—since they were “generally recognized as safe.” (Many, it turns out, actually weren’t. Potassium bromate, for example.)

In time, however, the system became something very different from what it was intended to be. Instead of a means of grandfathering additives that had already been in use for decades, it became a way of introducing new additives and doing so without any oversight from the regulator.

The FDA simply couldn’t keep up with demands from companies to test their new additives. Companies started testing additives themselves and putting them in their products without waiting for the FDA to rule on their safety.

This went on for decades. Instead of asserting its authority, the FDA did what any understaffed, poorly run, hopelessly corrupt organisation would do: It turned a blind eye, until finally, ten years ago, it decided to legalise the system as it had developed.

Ex post facto is the term, I believe.

Since 2016, it’s been totally above board for a company to create a new food additive, “test” it—whatever that means—and then add it to foods for general consumption without any input from the FDA at all.

According to one study, since 2000 there have been only ten applications to the FDA for full approval of a new food additive, out of a total of 766 new food additives brought to market. That we know of.

The real scale of the problem is likely to be far, far greater. Not hundreds of unknown quantities, but thousands. Estimates suggest there could be as many as 10,000 food additives in regular use in the US. In the EU, where oversight is much more stringent, there are about 2,000.

Kennedy is right, as I said: GRAS needs to go. And it looks like he’s taking steps to do that now.

But GRAS is just the start. It’s just one instance of a dangerous mindset or attitude we see again and again in American public life. I call it “safe until proven otherwise.”

“Safe until proven otherwise” encourages us to believe that products should be treated as safe until science tells us they’re not.

It might seem reasonable, on paper, and it might encourage experimentation and innovation, as the processed-food makers love to remind us; but such an attitude can easily lead us astray, especially when corporations can jam their thumb on the scale by submitting their own research for approval and packing regulatory boards with staff from their own pockets.

We see this in the way chemicals are regulated, too. It’s the reason why it takes decades to establish that a chemical like bisphenol A (BPA) is harmful—decades after that chemical has been added to sippy cups for babies and microwaveable food containers and every other kind of plastic product—and then, when the chemical finally does get taken off the market, new alternatives are brought in that are every bit as harmful, sometimes more. BPA alternatives like BPS may be more toxic, but baby’s sippy cup and your water bottle are proudly—and legally—sold as “BPA-free.”

ATBC, a “safe” alternative to phthalates, was recently shown to be neurotoxic, with a clear suggestion that maternal exposure while pregnant could cause brain damage for the baby.

This has to stop. We need to reset the scale.

How about “harmful until proven otherwise?” What if we started there?

Corporations would be sure to object. But they’re not the ones who’ve suffered, are they?