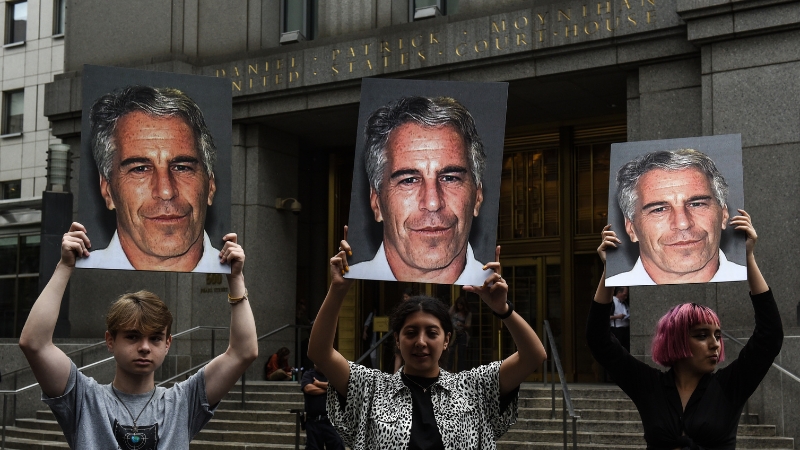

Image Credit: Justin Sullivan / Staff / Getty Images

Image Credit: Justin Sullivan / Staff / Getty Images “The study of obesity is the study of mysteries.”

That’s the opening to one of my favorite blogs of all time, the series “A Chemical Hunger” on the charmingly named Slime Mold Time Mold.

The truth is, there are many, many things we still don’t know or understand about obesity, despite decades of scientific research. The blog explores some of the more glaring mysteries, and some of the weirder ones, too.

The more obvious mysteries include the sheer speed with which Americans have become so fat.

In the 1920s, the average man in the US weighed 155lb, and about 1% of the population was obese. Today, he weighs 195lb, and about 40% of the population is obese.

The change took place much more abruptly than you’d think. It wasn’t a gradual rise. Between the 1890s and the late 1970s, “people got a little heavier” in the US. Then, suddenly, beginning in 1980, the obesity rate went through the roof, from about 10% to closer to 30% within 20 years.

Between 2010 and 2018, obesity rates in the US increased more than twice as much as they did between 2000 and 2008.

Then there’s the weirder stuff.

How do the Mbuti people of the Congo stay lean despite getting up to 80% of their calories from honey in the rainy season?

Why are lab animals and even zoo animals getting fatter, despite being fed the same food as before?

Why do people who live at higher altitudes in the US have a lower risk of obesity? Colorado, the highest-altitude state, has the lowest incidence of obesity. US service personnel assigned to low-altitude areas are at greater risk of becoming obese than their colleagues in high-altitude areas. It’s not just the US, either: the same patterns have been observed in countries as diverse as Spain and Tibet.

Here’s my personal favorite: Is obesity catching?

Literally: Is being fat transmissible?

And I mean that in a biological, rather than a social sense. I’m not talking about picking up bad habits from living among a herd of fat people or becoming obese for socio-economic reasons.

No: Can you catch fatness like a cold?

It’s been a while since I read “A Chemical Hunger” from start to finish, so I can’t remember if infectious obesity is actually one of the weird mysteries discussed. I certainly can’t be the first person to suggest it, though. For one thing, it would be a very handy explanation for the otherwise baffling speed with which obesity has spread in recent decades.

And just like with infectious diseases, microbes would be the agent.

Here are some facts.

Certain species of bacteria are associated with obesity, and what’s more might actually cause weight gain if they end up in your gut.

In a 2006 study, researchers compared the gut microbiomes of genetically obese and lean mice. The bacteria in the guts of the obese mice were difference from those in the guts of the lean mice, with a much higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes bacteria. When the researchers transplanted gut bacteria from the obese mice to the lean mice, they put on more body fat, even when their diet remained constant.

This is clear evidence that weight gain can be caused simply by changes to the bacteria in the gut.

A follow-up study from the same researchers showed that a gut transplant from obese humans to lean mice had the same effect.

It’s also widely known that germ-free mice—mice raised to have a sterile gut—are much more resistant to diet-induced weight gain.

So what if microbes that encourage obesity—we know they exist—were passed between humans through close contact? What then?

We already know that other conditions, including psychological conditions, have a previously unknown infectious component.

For example, recent research has shown that microbes associated with depression and anxiety pass between romantic partners when one of them experiences an episode (the microbes were found in the mouth). What’s more, the transfer of these microbes was associated with worsened mental health in the recipient, including disrupted sleep.

So, if you can make your wife or husband’s mood worse by sharing an intimate space with them—eating together, kissing, touching, borrowing their toothbrush—could you make them put on weight by the same mechanism?

It’s a fascinating possibility.

Imagine it: people coming into close contact with each other, sharing microbes, and making each other fat. It wouldn’t just have to be couples: It could be parents and children, friends, housemates and roommates, coworkers—anybody who shares space regularly.

It rather makes you want to go and live in a cabin in the woods somewhere, far away from everyone else…

The truth is we simply don’t know. What I’ve suggested is plausible, and if I held the purse strings at the NIH, it’s the kind of research I’d be funding right now. Sadly I don’t.

On social media this week, people have been hailing the end of obesity, with the announcement of President Trump’s “universal basic fat jabs.” After securing an historic agreement with pharma companies like Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly to bring prices of their drugs crashing down, the President has now launched a new website called TrumpRX to allow Americans to find the best deals for drugs like Wegovy/Ozempic and many others.

We should be glad the Trump administration is taking obesity seriously—and not just through TrumpRX, but also through RFK Jr’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again. But obesity isn’t just going to disappear overnight. My prediction: We’ll still be unraveling its mysteries for many years to come.

Raw Egg Nationalist’s new book, The Last Men: Liberalism and the Death of Masculinity, is out now in hardback, audiobook and Kindle formats at Amazon and in all good bookstores.